|

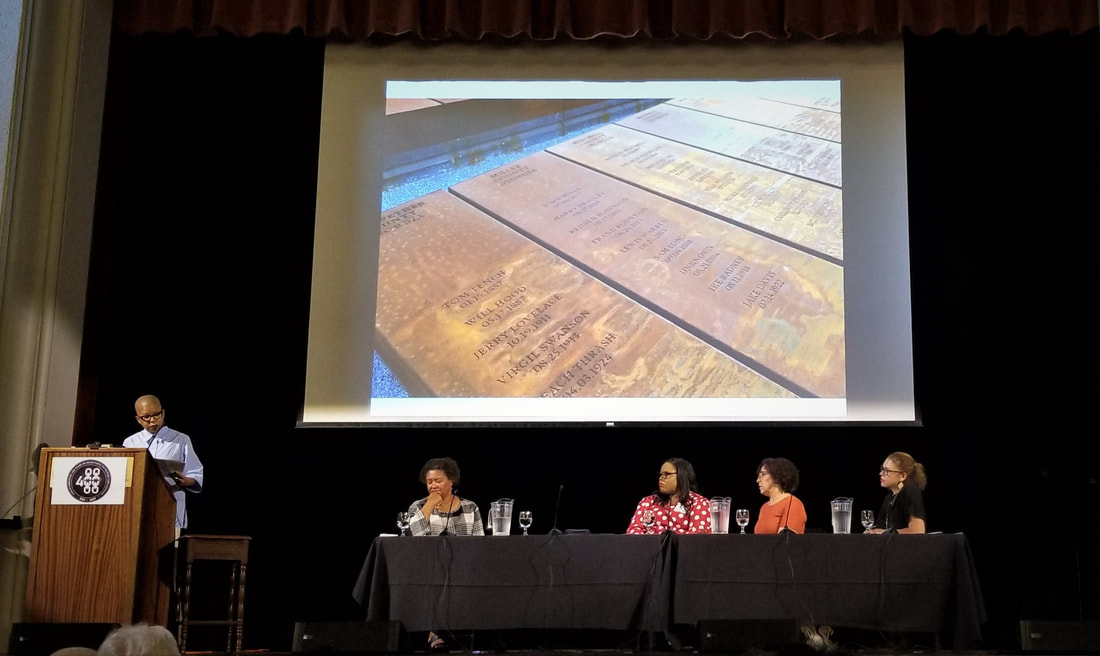

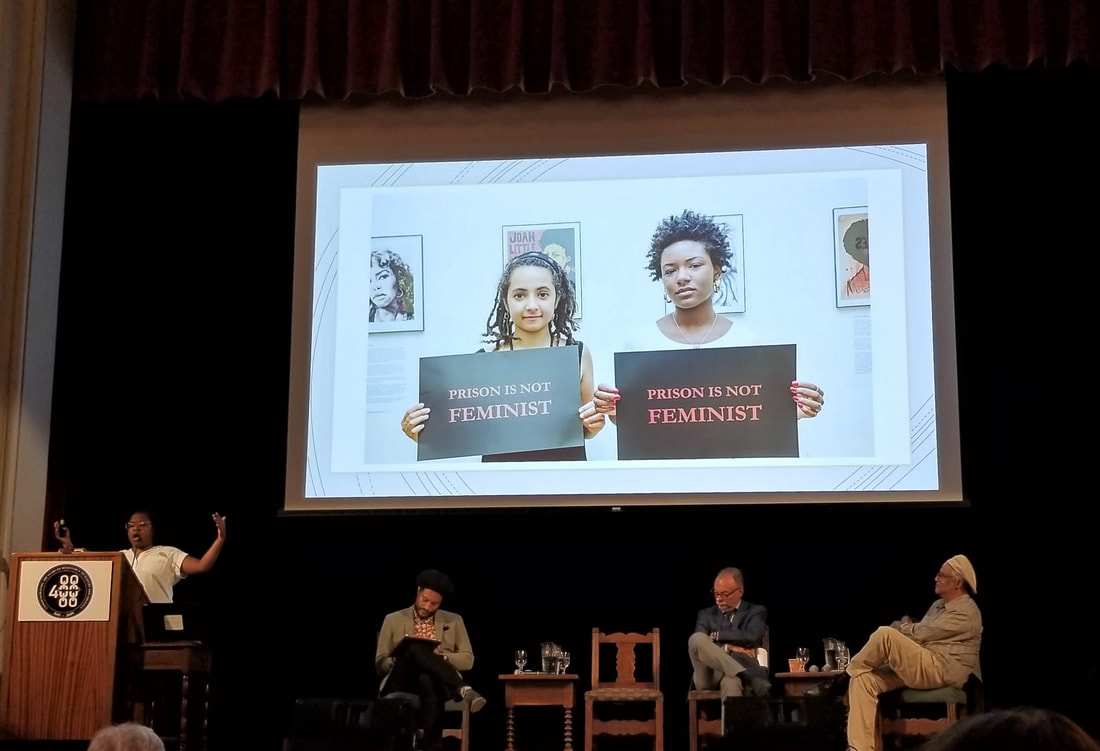

By Micki Luckey While visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, Christina Sharpe, a Black Professor from York University, was deep in contemplation of the trauma represented by the names of lynching victims on 805 hanging steel columns and similar coffin-like columns laid in the ground. She was approached by a white woman who said, “I’m so sorry.” Sharpe said she did not reply; full of her own sorrow, she did not want to take on the unknown white woman’s distress.  Logo of the symposium depicting the number 400 using broken chains for the zeroes, inside a circle stating Commemorating 400 Years of Resistance to Slavery and Injustice 1619–2019. (Photo by M. Luckey, with permission from Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society) Logo of the symposium depicting the number 400 using broken chains for the zeroes, inside a circle stating Commemorating 400 Years of Resistance to Slavery and Injustice 1619–2019. (Photo by M. Luckey, with permission from Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society) This is just one of many memorable stories shared by an impressive group of Black professors and performers at a symposium convened at UC Berkeley on August 30, 2019. Commemorating 400 Years of Resistance to Slavery and Injustice, the symposium was designed to “recognize those who fought against slavery and continue to fight for justice today.” It opens a year-long observation of the 400th anniversary of the forced arrival of enslaved Africans in the colony of Virginia. (For information about upcoming events go to 400years.berkeley.edu.) Opening the symposium, Doniel Mark Wilson immediately unified the audience by leading us in singing ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing.’ Denise Herd of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, Chancellor Carol Christ, and Oscar Dubón, Vice Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion, offered welcoming remarks. Aya De Leon delivered a powerful reading from her latest novel, Puerto Rico and Mr. Jones, reflecting on the devastation wrought by hurricanes Katrina and Maria. She noted that the “alleged” debt Puerto Rico owes the U.S. is equivalent to their loss of revenue from the Jones Act (a 1920 law that requires all shipments of goods between any two ports in the United States be carried on US flagged ships.) Later in the day Ree Botts and Reequanza offered more spoken word, and Latanya Tigner and Dimensions Dance Theater performed a dance tribute to Harriet Tubman. The bulk of the day was devoted to three panels. The first, on ‘Slavery, Memory, Afterlife’ was interdisciplinary, ranging from history to poetry and reflections on museums. Leslie Harris, author of several historical books on slavery, made the point that having Black historians and then Black female historians equipped with techniques from feminist studies has changed the community of slavery scholars. Stephanie Jones-Rogers, author of They Were Her Property, spoke on the contrast between how white women described their behavior as slaveowners and how, in oral histories, their slaves described their treatment by these same women slaveowners. Gabrielle Foreman, who is finishing a book on The Art of DisMemory, spoke of poetry and art that preserve the history of slavery. She paid tribute to a slave named David Drake whose inscribed pots are displayed in museums around the country. Christina Sharpe, author of In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, discussed how the memory of slavery is presented in museums that attempt to “engage materialization of imagination… [to] make tangible the terror of slaves.” The Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, uses art, photography and first-person narratives to depict the historical and ongoing oppression. For example, Sharpe showed a photograph of African-American inmates from 1960s picking cotton that could be easily mistaken as depicting the slavery period. Sharpe intentionally did not show photos of lynching and other violence, asserting that repeatedly showing such images does not produce empathy; how to recall and produce empathy is a question the poets and visual artists are helping address to be sure the pain is not forgotten. The second panel entitled ‘Second Afterlife’ focused on the large-scale incarceration of Black people and emphasized the importance of listening to the words of prisoners. Dennis R. Childs, author of Slaves of the State, documented how it feels to be incarcerated with no rights and to exist in a living death. He described the Angola Prison Plantation where until at least 1999 prisoners picked the 18,000 acres of cotton, right next to a present-day B&B where white people can enjoy the romantic veneer of the old south. Talitha LeFlouria, author of Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South, agreed on the importance of listening to Black prisoners, especially when they say they are treated like slaves. She focused on the mass incarceration of Black women and warned that it should not be overlooked as the opioid epidemic creates a new wave of white women prisoners. Declaring that prison abolition is not a metaphor, both speakers called for joining organizations such as Critical Resistance and All of Us or None, and by supporting re-entry homes, such as the Safe Housing Network. The third panel was on ‘Power and Resistance’. Waldo Martin opened this session with a recording of the song “God Don’t Want No Coward Soldiers in His Band” by Shirley Caeser to underscore his message that Black people have agency. Martin, co-author of Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, spoke of the myriad ways Black people worked to free themselves and to undermine white supremacy, whether during the Confederacy or in the 20th century. For example, after emancipation a former slave named Jordan Anderson responded to his former master’s invitation that he return to work by requesting his back wages, calculated to be thousands of dollars. Charles P. Henry, former president of the National Council for Black Studies and a prolific author, used his family history, with genealogy traced back to a free Black man at the time of Thomas Jefferson, to dispel two myths: that white supremacy is a southern problem, and that slavery is over. He quoted Gunnar Myrdal, who in 1944 said, “Almost everybody in the North is against discrimination but almost everyone practices it.” He stressed how economics — the desire for riches — was not only the driver of slavery, it was the very basis of our nation’s inception, leading to a discussion of the need for reparations today. Christine A. Carruther, the founding director of BYP100 (Black Youth Project 100), a national organization for development of young Black leaders and activists, asserted that organizing is a life-long commitment. She described her work as a queer Black feminist as filling the holes in incomplete stories. Citing the developments in surveillance technology, she stated that even if the prison walls come down today, the prison state would still exist. Carruther called for people to organize to create a world without prisons, without gender-based violence, and with valued work (including sex work). John A. Powell, the Director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society and author most recently of Racing to Justice: Transforming our Concepts of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society, offered closing remarks. Stating “The opposite of Othering is not Saming but Belonging,” he called on us to change the conditions and the stories that help people step into a new space. This was an apt culmination of the entire symposium: a powerful call for societal transformation and liberation.

Comments are closed.

|

Find articles

All

Browse by date

July 2024

MEDIUM |

© COPYRIGHT 2017-2024 SURJ BAY AREA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed