|

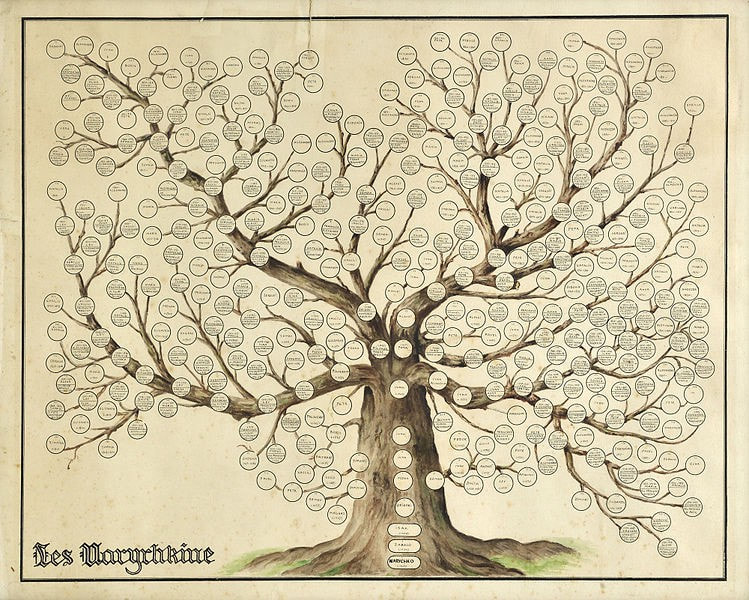

Part 1 of 2: It’s time to stand up against White Rage by Regie Stites On August 29, 2023, a public elementary school in my neighborhood in Oakland, California was closed for the day because of an emailed bomb threat. Incredibly, the threat of violence came about as a reaction to a weekend playdate at the school for children of color and their families, an effort by the school community to create a safe and welcoming space for all children. By Eve Higby Many of us are looking at our stations in life — where we have privilege and where we lack it. Our society has various power structures that define those privileges: patriarchy, racism, capitalism, cisheteronormativity. As a white woman, I have some power in a group of mixed races due to the forces of white supremacy, but less power in a group of white men and women due to the forces of patriarchy. Within a group of white women, my class standing will play a role in how much power I have. The way that each of our identities is positioned within those structures and within certain social contexts form the basis of a critical self-analysis. This type of analysis helps us to think about our privileges and where they come from, considering race, ethnicity, gender identity and expression, age, immigration status, and socioeconomic status. What is critical family history? A critical self-analysis is useful for understanding how we navigate society and experience certain privileges and are denied others. But our circumstances and even our identities are also a product of our ancestors and the circumstances that they went through. By completing a critical family history, you can start to understand your family history in the context of larger social relationships of power, such as racism, colonization, patriarchy, and social class. You may even discover how your own family members participated in, helped to construct, resisted, or simply experienced these forces. Micki Luckey Among the many great books that document the history of slavery in the United States, none made me see its present impact as did How the Word is Passed by Clint Smith. Subtitled A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, the book takes us to places in this country where we encounter present-day reminders of slavery, “places whose histories are inextricably tied to the story of human bondage.” Reading about what Smith saw and who he met brought up many feelings — distress, sadness and rage, along with an appreciation for all I was learning. Smith presents new, often surprising information at every site he documents. To explore different aspects of the history of slavery in this country, Smith takes us to a cemetery, a monument, a prison and more. He talked with residents, guides, and scholars, who shared their personal experiences and remembrances. While the book title comes from the Getting the Word oral history project of the 1930s, it is through the voices in this book that the word continues to be passed. Smith ends How the Word is Passed by sharing bits of his family story as well: “My grandfather’s grandfather was enslaved. … My grandparent’s voices are a museum I am still learning how to visit.” Smith has created his own kind of museum by sharing the stories in this book. Below I share some highlights, but I recommend you open this book and enter the museum yourself for the fascinating details you will find there. By Heather Millar

Like most people in this country, I’ve been arguing a lot this year. Pointing out racism and lack of empathy on social media. Bristling a bit when made aware of my own racist missteps. Doomscrolling and raging against the headlines. I’ve been a journalist for most of my life, though I’m now pandemically unemployed. Among many other things, I’ve covered jails and prisons, politics and social policy. I thought I “got” this country’s racism. I knew it was foundational to our nation’s problems, central to our history. I volunteered regularly; protested occasionally. By Micki Luckey

While visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, Christina Sharpe, a Black Professor from York University, was deep in contemplation of the trauma represented by the names of lynching victims on 805 hanging steel columns and similar coffin-like columns laid in the ground. She was approached by a white woman who said, “I’m so sorry.” Sharpe said she did not reply; full of her own sorrow, she did not want to take on the unknown white woman’s distress. By Sandy Bredt

“Our founding ideals of liberty and equality were false when they were written.” With that salvo, Nikole Hannah-Jones opens the introduction to her latest gem, the New York Times’ “1619 Project,” a comprehensive exploration of slavery and racism, produced with the Smithsonian and the Pulitzer Center in commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the first African slave ship landing on our shores. By Christina Robinson and Elizabeth Humphries

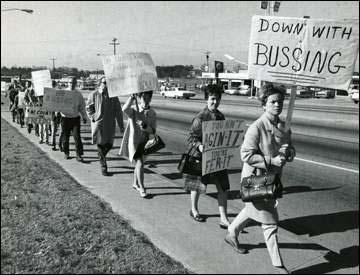

In just one week three communities across this country faced terror and the loss of loved ones at the hands of white men armed with guns. Our hearts are heavy with sadness for those who are grieving and those who have been touched in other ways — like those who will never be able to attend the Gilroy Garlic Festival without remembering the terror that happened there. And because it can feel like any town, city, church, or festival could be next, we share the fear and trepidation of people throughout our country. By Micki Luckey White women protesting bussing White women protesting bussing I admit I was distressed reading Mothers of Mass Resistance, the new book by Elizabeth Gillepsie McRae that documents how women upheld white supremacy in the US from 1920 to 1970. Not that any part of this meticulously detailed history was false. After reading and writing about the struggles for civil rights and integration, I simply did not want to recognize the power white women have wielded in opposing desegregation and civil rights. But McRae contends that the roles women played to support segregation of the races, while generally kept out of the limelight, were nonetheless effective. She states, “…when we focus too much on national legislative victories over legal segregation, we miss the endurance of white supremacist politics and practices in local institutions, in local communities.” (McRae, p.10)  What’s one of the most effective ways to dismantle white supremacy? Our SURJ Bay Area Youth and Families (Y&F) Committee starts at the roots by educating and mobilizing youth, parents, youth workers and educators, as well as partnering with local organizations with a child- and family-centered lens toward racial justice. One of our major partners is Abundant Beginnings, a local community-based organization founded and run by Black queer freedom fighters. Abundant Beginnings uses a kid-friendly vocabulary — defining solidarity, for instance, as “the act of supporting other people (especially those who are not being treated fairly).” We are proud to stand in solidarity with Abundant Beginnings as we work toward a world in which children can grow up free from the injustices of white supremacy.  #12DaysToShowUp, Donate to SURJ's 12 Days to Show Up campaign. Background image courtesy CRC Media. #12DaysToShowUp, Donate to SURJ's 12 Days to Show Up campaign. Background image courtesy CRC Media. In 1969 Fred Hampton Sr, the 21-year-old charismatic chairman of the Chicago Black Panther Party, was targeted and killed by the FBI in a raid organized by the Cook County State Attorney. Law enforcement carried out the raid and murders after several months of media coverage blasting the the Black Panther Party as “Wild Beasts”, and the FBI issuance of internal memos deeming them a “major threat” to the country. The FBI was committed to dismantling the Black Panther Party “by any means necessary.” We look back at that time and those events in disgust and awe. However, we know that targeted repression of Black resistance is unquestionably NOT a thing of the past. We need only look at a 2017 FBI internal report entitled “Black Identity Extremists Likely Motivated to Target Law Enforcement Officers” which seems to have been used to justify surveilling and jailing a black activist — severely disrupting his life — based solely on his Facebook posts calling out police brutality. |

Find articles

All

Browse by date

July 2024

MEDIUM |

© COPYRIGHT 2017-2024 SURJ BAY AREA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed