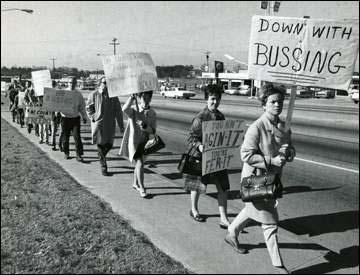

By Micki Luckey White women protesting bussing White women protesting bussing I admit I was distressed reading Mothers of Mass Resistance, the new book by Elizabeth Gillepsie McRae that documents how women upheld white supremacy in the US from 1920 to 1970. Not that any part of this meticulously detailed history was false. After reading and writing about the struggles for civil rights and integration, I simply did not want to recognize the power white women have wielded in opposing desegregation and civil rights. But McRae contends that the roles women played to support segregation of the races, while generally kept out of the limelight, were nonetheless effective. She states, “…when we focus too much on national legislative victories over legal segregation, we miss the endurance of white supremacist politics and practices in local institutions, in local communities.” (McRae, p.10) McRae revealed four categories of work that white women carried on to resist desegregation and racial equality by affecting social welfare policy implementation, public education, electoral politics and popular culture. Ordinary women maintained ‘the color line’ by policing the behavior of their neighbors, by enforcing their prejudices in their jobs as social workers, and by campaigning to have white supremacy taught in schools, and fiercely fighting against busing as they tried to prevent school integration. These women knew that “maintaining racial segregation required work beyond dependence on mere laws.” (McRae, p.218)

In her book, McRae tells the stories of a network of little known female segregationists, including: -Mrs. Hugh Bell in Wilmington, North Carolina, who from her home organized petition drives against Brown v Board of Education and distributed a 60-page document purporting to prove black intellectual inferiority and to describe the deleterious effects of racial integration on dating etiquette, teacher training, public health policies, sexual customs, civic organizations

In fact, although McRae stops her history in the 1970s, the resistance she described surely has continued to the present. First the Tea Party conservatives, and now the white nationalists who have gained so much power and visibility under Trump, were undoubtedly aided by the groundwork of many women, along with their vocal female leaders. But this is just one side of the story. I found a different view of the same period in our history in Killers of the Dream by Lillian Smith, which I happened to be reading when I read Mothers of Mass Resistance. This book gave me inspiration and insight -- inspiration from reading about white women who worked for racial justice, and insight from Smith’s perception into why white supremacy has been so tenacious. The decades covered by Mothers of Mass Resistance correspond to the adult life of Lillian Smith, a Southern woman dedicated to fighting segregation and upholding human rights. Born in rural Florida in 1897, Smith spent most of her life in the mountains of northern Georgia where she directed a summer camp for girls until she became a full-time author. She was thrust into fame (and infamy) by publication of her novel Strange Fruit (1944), which told the story of an interracial romance with tragic consequences. An instant best-seller, the novel’s success gave Smith a national audience as she continued to write and speak for racial justice. Her next book, Killers of the Dream (1949), was a deep analysis of race that combined her understanding of child psychology with her ideas for social change based on the recognition that racism hurts both black and white people. Smith starts Killers of the Dream with an autobiographical analysis of the harms of segregation to white people based on her own childhood in a loving family. She describes poignantly the confusion of a white child who has been raised by a beloved black mammy and then must learn that ‘Negroes’ are to be treated as less than human and never included at the family table. Add the confusion from the contradictions between the Christian lessons, not confined to Sunday but repeated daily in the home, and the strict social lessons (and laws) that segregated the races even at different churches. All of this combined with the confusion and guilt arising from the taboos about sex that are never explained to the child but are somehow linked to the taboos about mingling with ‘Negroes.’ And finally, the guilty satisfaction of knowing your skin color gives you a superiority that allows you to do mean little acts like forcing black kids off the sidewalk. About these reflections Smith wrote, “Something is wrong with a world that tells you that love is good and people are important and then forces you to deny love and to humiliate people. I knew, though I would not for years confess it aloud, that in trying to shut the Negro race away from us, we have shut ourselves away from so many good, creative, honest, deeply human things in life.” (Smith, p.39) Smith’s camp was a microcosm for creating different lessons, a place where she and her close friend Paula Snelling could foster esteem and creativity in each child while teaching respect for all humans. She describes an older camper’s frustration of learning that the ideals practiced in camp cannot be carried out in Southern life. The girl asks, “’How would it be if we lived the way we have learned to live? ...Suppose I said to a colored girl, “Let’s go in the drugstore and have a coke”? Can’t you see their faces—Mother’s and Daddy’s—and everybody’s! Well I can—especially if they arrested me and put me in jail. I’d be breaking a law, wouldn’t I, if I tried to live these ideals in my home town?’”(Smith, p.52) The conversation continues, discussing religion, love and hate, the origins of segregation. The wrought camper exclaims, “’It just tears us up inside…You’ve unfitted us for the South.” (p.54) Smith’s answers to this camper start with family history: “’You have to remember,’ I said, ‘that the trouble we are in started long ago. Your parents didn’t make it, nor I. We were born into it. Signs [for Whites and Colored] were put over doors when we were babies. We took them for granted… People find it hard to question something that has been here since they were born.’” (p.57) Smith then describes the generations who did establish segregation, explaining that In order to defend slavery her grandparents’ generation had to invent the myth that blacks were subhuman. Thus “hypocrisy, greed, self-righteousness, defensiveness twisted in men’s minds.” (Smith, p.61) Upholding segregation became one with loyalty to the South, while troubles were blamed on interference by the North. Smith gives her view of Jim Crow as not only a compromise between the South and the North but as a bargain between rich Southern men and poor Southern men that gives the rich the power and the poor the white-skin privilege that together keep the ‘Negro’ in his place. In her analysis of the harm done to the white psyche Smith describes at length what she called the race-sex-spin spiral. Starting from early learnings of the strongest taboos (against associating with ‘Negroes’ and against masturbation), fanned by powerful annual religious revivals with their focus on sin, confirmed by the lighter shades of many black babies (rejected by their white fathers), and culminating in the fears for the rape of white women by black men (which occurred much less than the rape of black women by white men.) The white man who puts his white wife on a pedestal and seeks satisfaction from a black woman has a conscience split between “what is done and what isn’t; into ‘pure’ and ‘impure’; Madonna and whore; … ‘right’ and ‘wrong’; belief and act; segregation and brotherhood.” (Smith, p.133) This split results in constant discomfort undermining the stature and privilege of the white man. As for white women, Smith describes how empty and sterile a life on the pedestal could be. “The majority of southern women convinced themselves that God had ordained that they be deprived of pleasure, and meekly stuffed their hollowness with piety…” (Smith, p.141) To shut out evil they created homes and gardens of beauty, “of quiet ease and comfort and taste… where sex was pushed out through the back door as a shameful thing, never to be mentioned. Segregation was pushed out of sight also…” (Smith, p.141) They became rigid in their views of child rearing, of eating, of religion, as they became vigilant guardians of a southern tradition—as McRae said. This is the root of the culture of the Mothers of Resistance that McRae describes. These damaging effects on white personalities are what kill the dream that humans can live up to the ideals of racial equality and are the target of Smith’s activism. She launches scathing criticisms of church and the government spokesmen who accept segregation and carry out its hypocrisy while never mentioning the injustices and brutalities. She denounces racist politicians who are full of hatred, as well as liberals who counsel patience. Smith calls for leaders who will take a clear stand against segregation. She looks toward changes that will free the ideals of equality and support critical thinking and honest self-appraisal, and in doing so, unleash talent and energy among white and black people in the South. Grounded in Freud, anticommunism, belief in the US as a democracy, Smith writes as a woman of her times, and yet when it came to racism she rose above her times. She became prominent as the most outspoken critic of segregation; she deserves recognition as a true pioneer. Her book Killers of the Dream was republished in 1961 at the start of the Civil Rights movement, allowing her to write a new preface in which she noted with satisfaction the first lunch counter sit-ins and a new ending that praises the Montgomery bus boycott and the Freedom Riders. By 1961 Smith was not the only female southern voice speaking against segregation. For example Anne Braden and later Mab Segrest also organized resistance to segregation, exploitation and violence. There was even an Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching formed by a group of church women who said they neither needed nor wanted the ‘chivalry’ of lynching to protect them. Over the years they attacked the KKK, and they took a stand against segregation in the church itself. The collection of her letters published as How Am I to Be Heard?, edited by Margaret Rose Gladney (1993), indicates that Smith maintained good relations with her Southern neighbors, even as she and her lifelong partner Paula Snelling hosted biracial dinner parties, salons, and conferences. Over the years Smith gave many talks, published editorials, corresponded extensively (even with Eleanor Roosevelt), appeared on television, and joined boards for progressive organizations such the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE.) She was sustained in this work by the possibility of change. In 1946 Smith wrote to the first executive secretary of CORE, George M. Houser, “Since for decades in the South we have lived in a psychological state where even words have not been permitted, we must first break down the conspiracy of silence. We must say out loud that we believe in human equality; we must say out loud that we do not believe segregation is just or democratic or sane. We have to say these things first. Then once saying them, we must begin to act.” (Gladney, p.108) While finishing Killers of the Dream in 1949 she wrote to her publisher, I believe that “much must be done in order for it [the South] to give up the drug-like habit of White Supremacy… but we could change the whole picture within a year or two if we wanted to and felt an urgent necessity to do so.” (Gladney, p.126) To read more of her vision in her beautiful writing, I urge you to read Killers of the Dream (republished in 1994.) It is a powerful antidote to Mothers of Massive Resistance because it not only reveals the deep roots of white supremacy, it also shows the wisdom of this woman who fought it. As a white woman I need to know the history of white women’s participation in racism in their roles as mothers, wives, teachers, neighbors and social workers but that’s not the whole story. I need to also know about the resistance to racism by Lilian Smith, Anne Braden and all those who have fought for racial justice so I can learn from and fully commit myself to continuing their work. Title Image from Greeneville County History Timeline 1970 Comments are closed.

|

Find articles

All

Browse by date

July 2024

MEDIUM |

© COPYRIGHT 2017-2024 SURJ BAY AREA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed