|

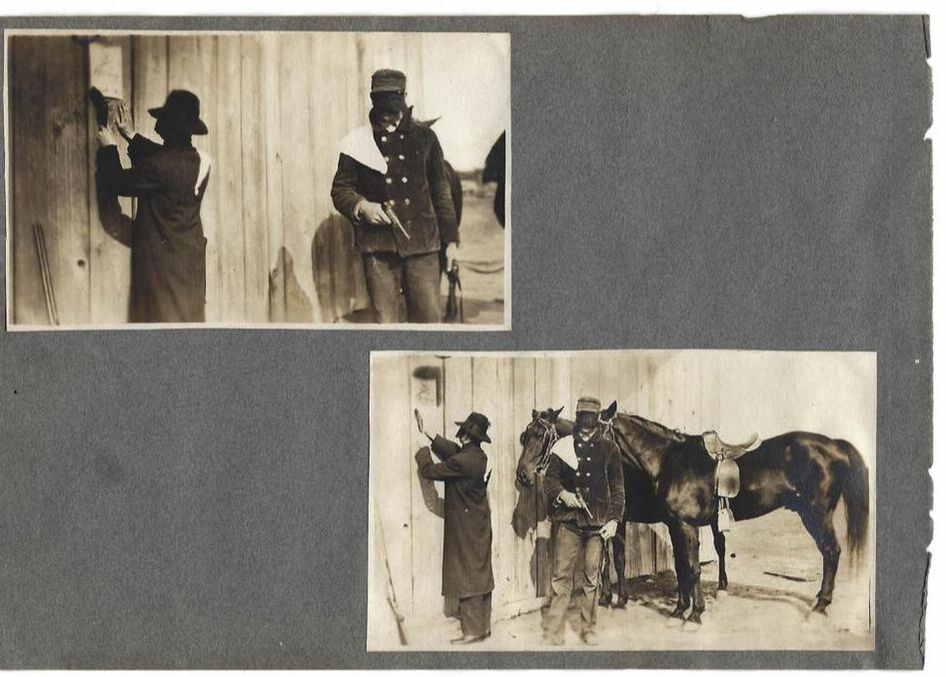

By Heather Millar I’ve always known that my mother’s side of the family came from the South. They were plantation owners. They enslaved Africans. After the Civil War, they joined clubs like the “Daughters of the Confederacy.” My mother used to tell stories about her great-great-grandmother going to college, taking an enslaved teenager as a servant. That side of the family was proud, and is still proud, to be related to Light-Horse Harry Lee and Robert E. Lee. My grandmother’s middle name was “Bolling,” to mark a tie with Edith Bolling Wilson, wife of President Woodrow Wilson, both unapologetic white supremacists. Mom grew up in Napa, California. But despite her feminism and her California childhood, many of her views had their roots in the antebellum slave economies of Tennessee and Kentucky. Knowing all this, I shouldn’t have been surprised to find hard evidence of the brutality this racism could sanction. A few weeks ago, I was going through a box of old photographs and pulled out an album from the first decade of the 20th century. It had been compiled by someone in my maternal grandmother’s family who had lived in Paducah, Kentucky. As I turned the construction paper pages, I registered a couple images I hadn’t noticed before. They were labeled, “Kentucky Night Riders.” The pictures show two men in dark face masks, wearing white sashes. One is pasting a notice with a skull-and-crossbones onto a barn door. The other holds a pistol conspicuously in his right hand, while gripping the reins of two beautiful black horses with the other. “Hey, honey!” I called out to my husband, a retired journalist. “Do you know what the Kentucky Night Riders were?” “I think they’re like the KKK,” he called back. I was stunned. I peered at the pictures more closely. Looking at them made my family’s role in the Civil War, in Jim Crow, in all the myriad ways that white people have oppressed people of color, seem so much more real.  Photo credit: Author's family album. This is an expanded version of the previous image. In old black and white photos, two men are wearing hats, dark face coverings and white shoulder sashes. One man is putting a notice on the side of a barn, while the other man holds a gun in one hand and the reins of two horses in his other hand. As I stared at the pictures, I couldn’t believe that someone would think that these were images to be preserved and shared with pride, along with snapshots of babies, birthdays, and vacations. But I also wondered at myself. Why did these pictures make the racial oppression feel so much more authentic? Why did this “proof” shock me? Hadn’t I always known this family history? This was an aspect of my cultural heritage that my mother and grandmother had treasured. Exactly what did this picture communicate that I hadn’t already known? Nothing. And yet. There, in the musty pages of a family photo album from four generations ago, there’s a picture that draws a straight line from the oppression right to me. Artifacts and heirlooms handed down through the generations are all over my home. A picture of my maternal great-great-grandmother hangs next to our front door. A photo pulled from this same album, of my grandmother at age seven with an Easter rabbit, hangs in our stairwell. Much of the silver and china that we haul out for parties and holidays were handed down from this Paducah, Kentucky branch of the family. Who were the Kentucky Night Riders? The Kentucky Night Riders were an unofficial, vigilante offshoot of the “Planters’ Protection Association” (PPA), a group that sought to fight a tobacco monopoly led by the North Carolina industrialist James Buchanan Duke. Duke’s American Tobacco Company had cornered the tobacco market and driven prices so low that most farmers in western Kentucky were having trouble surviving. In 1904, some 5,000 growers signed on to become members of the PPA, hoping that if they all stuck together, they could hold out for fair prices. The monopoly fought back, refusing to buy from PPA growers and offering extremely high prices to farmers who didn’t join the PPA. Some growers, pushed to starvation by this trade war, could not resist Duke’s offers of windfall prices for their crops. Enter the “Kentucky Night Riders” — you can find out more about them here and here — who sought to keep growers in the PPA fold by means of intimidation and retribution. They weren’t exactly the Ku Klux Klan. But they were all white and borrowed many of the KKK’s forms and methods: hoods and masks to conceal identity, night raids of terror including burning of buildings and lynchings, secret signs. Like the KKK, the Kentucky Night Riders could count extensive membership in the local elites, businessmen, bankers, judges, professionals. Also calling themselves the “Silent Brigade” or the “Possum Hunters,” the riders would tack a warning on the barn door of a farm that was selling to the American Tobacco Company monopoly. If the grower didn’t fall in line, and join the planters’ association, the secret paramilitary group would return and mete out violent punishment. That’s what my ancestors are doing in these pictures, nailing up the first warning on a barn door. The initial purpose of the Kentucky Night Riders wasn’t racial oppression but economic liberation. Yet, as seen time and again across American history, racial oppression is everywhere in their story. In addition to the price drops, large planters — all white — were upset that low tobacco prices pushed Black sharecroppers to leave the land because they couldn’t break even on their tobacco crops. Planters wanted the dependent, compliant labor force that sharecroppers could provide. Meanwhile, the hooded, dark-of-night tactics of the Kentucky Night Riders gave the group ample room to carry out personal vendettas. African-Americans largely stood with the official PPA, outnumbering whites in the planters group. Yet the Night Riders inflicted much of the worst violence on formerly enslaved people. In 1906, Night Rider raids burned two monopoly warehouses to the ground. Prices began to rise to the level that the planters had said they wanted at the beginning of the controversy. They could have declared victory. But the Night Rider raids continued on into 1908 and 1909, and the racial overtones grew more explicit. Riders would terrorize African-Americans to comply with PPA policy or to drive them away so that their land could be appropriated. In addition to burning barns and private homes, they ruined crops by salting fields. In March 1908, Night Riders launched a Klan-style attack on Birmingham, Kentucky, a small town that formerly enslaved people had built, bounded by the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers. Those who did not flee were slain. In the first years of the Kentucky Night Riders, the only people who went to jail were those who fought the self-appointed vigilantes. By 1911, however, public opinion began to change. People had grown tired of the lawlessness, and the courts began to send some of the Night Riders to jail. The American Tobacco Company monopoly was broken up that year, and the raids petered out. What Does All This Have to Do With Me? Did my ancestors participate in the worst abuses of the Kentucky Night Riders? I have no way of knowing. But seeing these pictures makes it impossible for me to deny the likelihood that they did. I keep asking myself: Why did I find this “proof” so shattering? Why did the picture feel so surprising? In the last year, I’ve become actively involved in anti-racism work. I have begun to see more clearly how racial prejudice permeates everything in this country. Perhaps that’s why the images jumped out at me after years of not registering what they portrayed. As I think of how these pictures made my ears buzz and my mind race when I realized what they were, I have to admit that I was still not really taking responsibility for my family’s role in systemic racism. I was holding it at arm’s length. I was making excuses for myself, if not for my ancestors. I was looking away from all the little luxuries in my life, the reminders that much of my comfort has been built on family resources built up over centuries, and largely built upon the kind of injustice the Kentucky Night Riders represent. I don’t write this to beat my breast, or to compete for the “Most Guilty” award, or to dissolve into white tears. I write just to say that this is the reality of white America, even if your family did not enslave people, as mine did. We all are beneficiaries of systems and history and assumptions and laws that preference us. These things do violence to people of color. If we are white, we are all likely to be connected to stories like the Kentucky Night Riders. This is why anti-racism work is a lifelong journey. Comments are closed.

|

Find articles

All

Browse by date

July 2024

MEDIUM |

© COPYRIGHT 2017-2024 SURJ BAY AREA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed