|

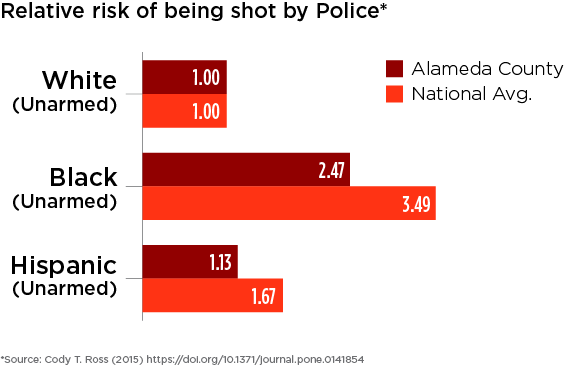

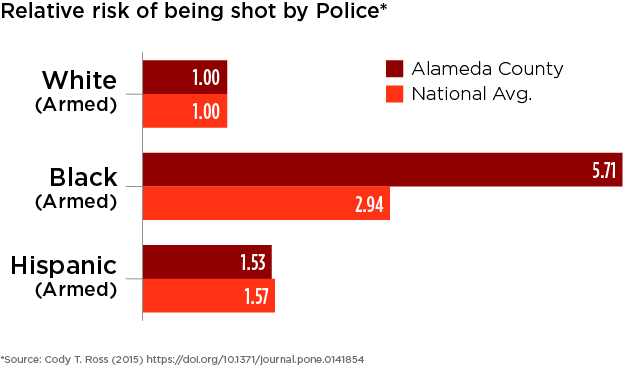

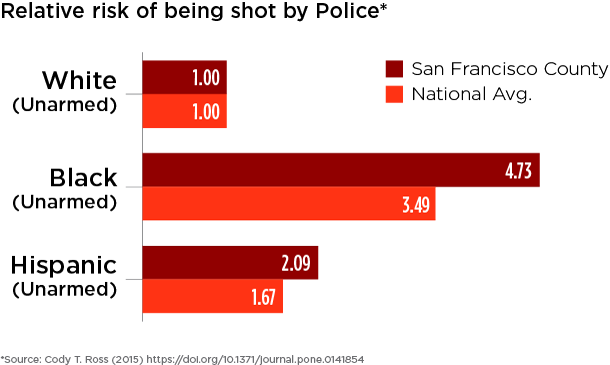

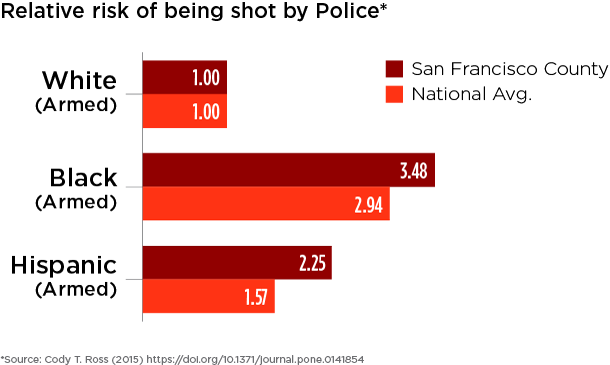

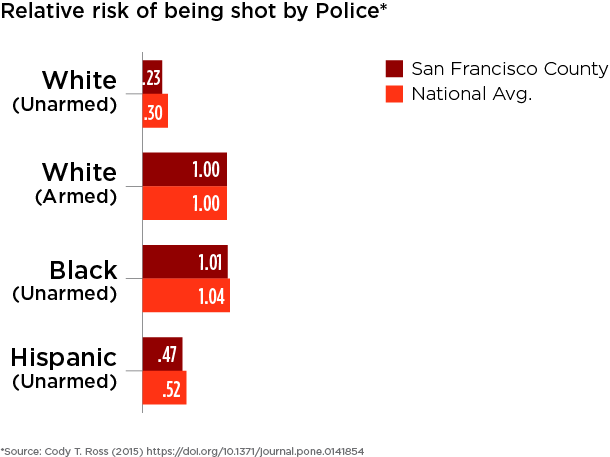

The police killings of Black and Brown people in the US is a threat that stretches well beyond the individual officers who pull the trigger. Recent data show that throughout the country Black and Brown people are far more likely to be shot by police than white people, regardless of local and race-specific levels of crime. The racial bias behind these murders is a systemic problem that is the product of biased policies in police departments and cities and the compounded effects of historical and present structural racism in the US. Racism in policing is one aspect of systemic white supremacy. In the Bay Area we see examples by looking at the murders of Kayla Moore, Alex Nieto, Luis Góngora Pat, Oscar Grant, Mario Woods, Sahleem Tindle, and others by police. This post was co- written and illustrated by Jesse Livezey and Tom Deckert. Content warning: Discussion of racism and police murders. To truly understand these police killings, the focus has to be on the system, not just the individual officers involved. One part of that process is to understand, both nationally and locally, what racial biases exist in police shootings. A 2015 study by Cody Ross, a University of California, Davis researcher, measured the relative risks of being shot by police across race (white vs. Black or Hispanic[1]) and armed vs. unarmed status both nationally and at a per-county level from 2011 to 2014. This was based on data collected by the U.S. Police-Shooting Database (USPSD), which does not suffer from the biases of self-reported databases like the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report. For the movements that focus on dismantling racist police structures and policies while lifting up community-centered alternatives, this data is vital. Two of the main findings of the study are that in Alameda and San Francisco counties as well as nationally:

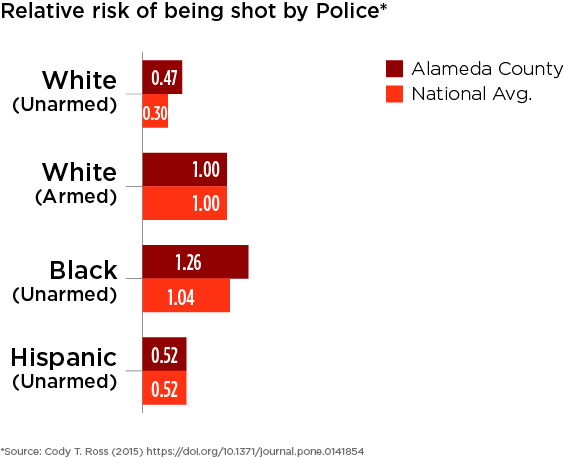

Both nationally and in Alameda County, Black people are significantly more likely to be shot by police when they are unarmed compared to white people who are unarmed. In Alameda County, unarmed Black people are about 2.5 times more likely to be shot by police compared to unarmed white people (3.5x nationally). There is a smaller, but still higher relative risk of being shot by police when unarmed for people who are Hispanic compared to white people: 1.1x in Alameda and 1.7x nationally. For people who are armed, Black people in Alameda County are 5.7 times more likely to be shot compared to armed white people (2.9x nationally). Both nationally and in Alameda County, Hispanic people who are armed are about 1.5 times more likely to be shot compared to armed white people. These two sets of results show that Hispanic people and, to an even greater extent, Black people are more likely to be shot by police than white people whether or not they are armed. This is true both nationally and for Alameda and San Francisco Counties. Finally, perhaps the most disturbing finding of this study is that Black people who are unarmed are slightly more likely to be shot by police than white people who are armed! This is true Nationally (1.04x more likely) and in Alameda County (1.26x more likely). Similar results are summarized here for San Francisco County. It is important to stress that the goal is not to just equalize rates of police violence. Even the baseline level of police shootings (white people being shot in these analyses) should be a cause for concern. Our goal should be to understand biases in the system of policing and also understand how increasing police militarization and surveillance makes our communities less safe. This is particularly true for Black, Indigenous, and Brown people, Queer and Trans people, people with disabilities, and people at the intersections of these identities. Together, these results underline the “epidemic” of police shootings of Black and Brown people both nationally and in the Bay Area. And while this data is crucial, it must be coupled with the human stories of lives cut short, families left devastated, and communities traumatized. How can we affect systematic change? There is a long history of organizing against police violence and its role as a cog in the prison-industrial complex. So find a local organization and get involved or support them financially. Show up for protests of police killings. Against the backdrop of gentrification, be mindful about what happens when white people call the police on their Black and Brown neighbors and help develop and implement alternatives to calling the police. The important thing is to do something and not just watch from the sidelines in dismay or shock. Silence is not an option. [1] The use of “Hispanic” as a common demographic field has roots in the US Census in the 1970s and is not descriptive of any particular ethnicity. Although “Hispanic” is less commonly used today, datasets often choose historical demographic categories for simplicity with the downside of providing less insight and also not aligning as well with people’s identities. You can read more about the history and more commonly used language here and here.

Comments are closed.

|

Find articles

All

Browse by date

July 2024

MEDIUM |

© COPYRIGHT 2017-2024 SURJ BAY AREA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed